TIFF23: “The Boy and the Heron” - Film Review

This review was originally posted on Film Obsessive.

Hayao Miyazaki’s latest and likely last film, The Boy and the Heron, begins with an ear-piercing shriek. It’s a siren that wakes Mahito (Soma Santoki) up in the middle of the night. The alert is because the hospital, the one where his mother works, is burning to the ground. While the specific year is unknown, the film takes place in Tokyo during World War II. In the opening sequence, Miyazaki abandons his usual animation style and instead offers frantic, blurry imagery to show the panic, fear, and lasting trauma this loss will be on Mahito.

After the death of his mother, his father (Takuya Kimura) relocates them to a secluded house in the countryside with Mahito’s aunt (Yoshino Kimura), who is now romantically involved with his father. Mahito is told by the cleaners who work at the house that strange things keep happening here. A prime example is a gray heron (Masaki Suda) that insistently tries to lure Mahito into a shadowy realm under the premise that his mother is still alive there.

Even that short description may be too much of an explanation of the film’s plot. Part of what makes The Boy and the Heron so compelling is the sheer mystery of the movie’s existence. In that regard, The Boy and the Heron has large shoes to fill. Miyazaki came out of retirement to create this film and it is expected to be his last. There’s an air of mystery about what he is saying here. What pressing matters drew Miyazaki out of retirement? To be fair, he has come in and out of retirement quite a few times, so it may be that no sense of urgency should be attached to this film.

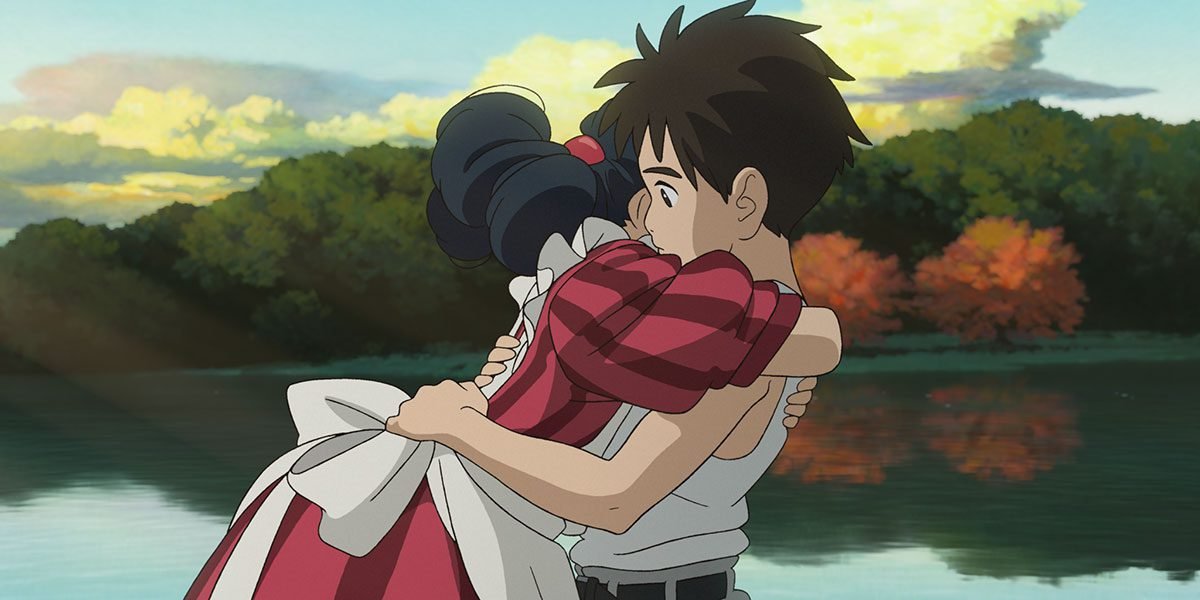

Courtesy of TIFF

The Boy and the Heron is very much a spiritual continuation of Miyazaki’s 2013 The Wind Rises. Both films, and others in his filmography, deal with the generational trauma of World War II. In The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki is as reflective as can be while keeping the setting in the middle of the war. The reckoning, realization, and understanding of the destruction cannot be understood yet by Mahito. He’s still in the thick of things, but Miyazaki can shape the story to simultaneously be in the moment and out of the moment. It is reflection and experience at the same instant.

As with any Miyazaki film, there are layers upon layers. It’s futile to review the film with an air of confidence of completely understanding everything that is at play. Some of the allegories are easier to pick up on than others, but will no doubt become clear with repeat viewings. That’s not a negative critique of the film, and The Boy and the Heron is not a puzzle that needs an explanation in order to make sense of it. Instead, it’s a compliment for the artistry that Miyazaki has shown time and again. Even so, in the film’s third act, Miyazaki lets the curtain fall away and makes his most plainly stated plea for kindness. It’s not the most deft way to handle the film’s central question, but then again, we are living in such wildly unprecedented times that maybe it needs to be said like this. Simply, obliviously, desperately, hopefully.

Courtesy of TIFF

This is not Miyazaki’s finest hour. At times the film drags, and there are maybe one too many stops along the path of this hero’s journey. One might want to fault him for that, and if the film is viewed in a solely vacuous way, it’s understandable, but Miyazaki is 82. There will be a time in the future when his retirement is final because he’s too tired to keep creating. Who can blame him for wanting to linger a bit longer in these fantastical worlds he’s created? Thematically, he’s putting together a jigsaw puzzle of what he’s covered in his past films, which makes The Boy and the Heron feel familiar and brand new all at once. If this is Miyazaki’s swan heron song, is it so wrong to linger just a bit longer than is narratively necessary?

The Boy and the Heron is a goodbye. A preemptive farewell from a man who gave so much of himself to a medium he adored. This film, which played at TIFF, offers his parting words on his own terms, which is about as much as anyone could ask for.

Follow me on BlueSky, Instagram, Letterboxd, & YouTube. Check out Movies with My Dad, a new podcast recorded on the car ride home from the movies.